Four years ago, I wrote “User Experience Design Revives Corporate Real Estate.” The new article below expands on my earlier ideas about harnessing occupant data to inform better building and design practices—benefitting both architects and end users.

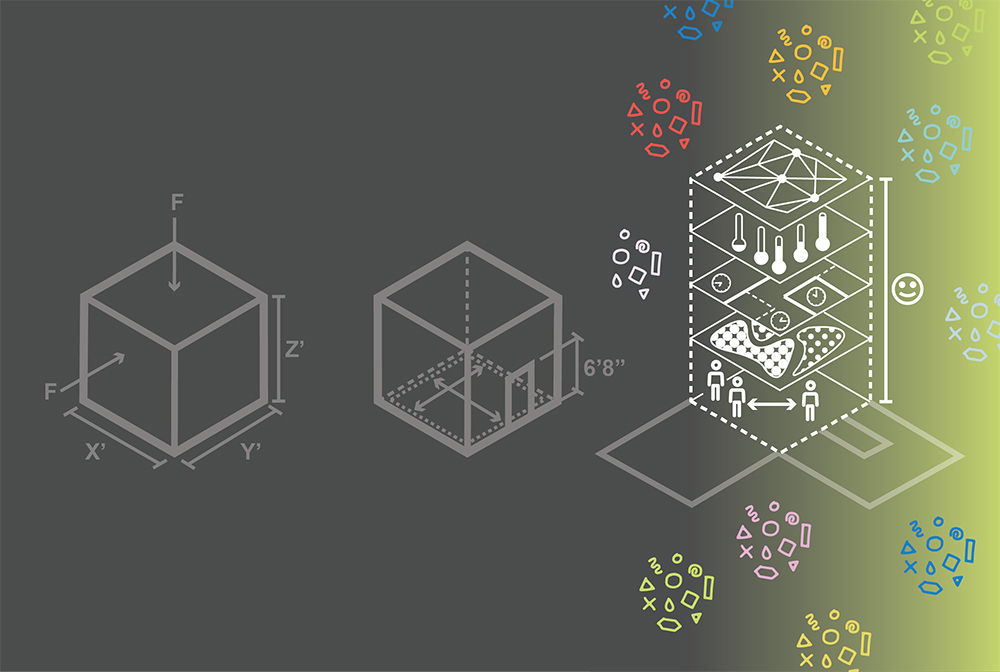

The Ancient Roman architect Vitruvius named three essential elements of architecture that contribute to a successfully designed building: firmitas (firmness), utilitas (utility or commodity), and venustas (delight, derived from the “aesthetic quality associated with the goddess Venus”).1

The first two of these, firmness and commodity, have long been easy to quantify through measures like structural integrity, building functions, energy usage, and cost. However, the more elusive quality of delight has always been difficult, if not impossible, to measure. With new technologies and methods emerging, however, that scenario is rapidly changing.

With social metrics ranging from advances in cognitive science to new tools for self-quantification and self-improvement, we are now developing comparable indices for delight. These, and their relationship to our work as architects and designers, are ours to define, explore, and use to advance our talents, projects, and the benefits we can bring to others.

Cognitive science is steadily developing better metrics for happiness, as the study of pleasure (known as hedonic psychology) has taken off in recent years. While we’ve been able to quantify many forms of simple sensory pleasure for some time, real happiness is much more complex and has proved much harder to pin down. Recently, however, scientists have begun to recognize the probability that emerging tools and research should allow them to hone in on ever more nuanced ways to measure and predict it.2

Alongside the development of these formal scientific methods, self-quantification and self-improvement tools geared toward greater happiness have been exploding in popularity. These tools encourage consumers to better understand their individual bodies and minds and take steps to proactively change their habits. Through an ever-expanding market of devices and apps, the “quantified self” movement is allowing users to track and analyze their sleep, physical activity, food and drink consumption, and much more. Self-improvement platform The Happiness Project3 began as the bestselling (and studiously researched4) book of the same name by Gretchen Rubin, which aimed to “synthesize the wisdom of the ages with current scientific research” about what makes happiness. The book quickly ballooned into a blog, interactive “toolbox,” monthly newsletter, companion videos, and even an international network of discussion groups where participants discuss their own “happiness projects.” Alongside both of these trends, the volume of social data available that speaks volumes about what and how we’re doing is greater than ever before. More and more of it is being produced every second through a variety of shareable media platforms.

From another angle, the rise of smart buildings and integrative tech means that “it is now possible to incorporate real-time, candid input from occupants, using technology to channel this information more seamlessly into our work.”5 Products like Nest now allow us to monitor the temperature in our homes from near or far, and employers are using badge swipe and desk sensor data to track and better meet the needs of their employees.6 The retail and hospitality industries have long understood they can invoke delight through multisensory offerings like pleasant scents and enchanting music; now their conclusions are being supported by technology and science7. When we better understand how our buildings work, and how we feel when we’re within their walls, we gain a peek into Vitruvius’s third element. As architects and designers, we may also be required by our clients to participate in collecting and harnessing evidence of this third dimension of building performance—which is a good thing. Our creativity, systems thinking, and analytical prowess will all required in this effort.

In the era of big data, we need to approach our work with bigger, and better, questions—questions that we as designers are driving, not just trying to answer. For our questions to be successful and meaningful, they must originate from the design side of the process. By exploring the intersection of human factors and the built environment from a design perspective, we will be able to leverage the results of our research to create effective and empathetic design solutions.

Architects are trained to think creatively and analytically at once, and we can use these skills to approach and craft our questions. Toshiko Mori, FAIA, emphasizes the need for architects to think beyond physical design and the built environment if we want to truly solve problems with our work: “Our profession is focused on the hardware, meaning the building craft. We are somewhat involved in the software, meaning infrastructure and engineering… But we need to look at the other problems surrounding us—to use our talents to think comprehensively, collaborate, and connect the dots.”8 Engaging with human interaction, user needs, and the element of delight is an opportunity to pivot from how architects typically approach problems to a new perspective that will frame our work in the context of people.

Understandably, there is considerable anxiety around the potential for gathering data and pursuing measurement to become an insidious activity. In recent years, the revelations of enormously far-reaching data collection and tracking by the National Security Administration, and of security breaches at major retailers like Target, have contributed to a wary attitude toward measurement and data collection.9 Health data is of course of particular concern (though what doesn’t get much press is how employers can use it to suggest personalized preventative care to employees10). The collection and use of personal information presents a gray area for many, and triggers debate over whether such practices are more helpful or invasive. Therefore, it is essential that we define these new measurements not as constraints or confinements, but as advocacy; as emotive and collaborative rather than as colonizing or predatory.

In the context of all these emotions and events, we must remember that it is our great opportunity as architects and designers to present “responsibly sourced” measurements as substantial and compelling opportunities for our profession and related fields. We can remove much of the mystery and misdirection from the process of design if we understand how people use and interact with the spaces they inhabit. Measurement and data collection can provide us with valuable insights that can inform better human-centered design in both existing and future structures.

Since the Great Recession, architecture as a profession has struggled. While recovery is underway, our difficulties are still evident to anyone within the field. In 2012, Salon ran an article by Scott Timberg on the architecture crisis, observing that “[a] once-thriving profession, one that requires considerable education and work ethic, and which has traditionally served a wide range of functions… is in trouble.”11 Timberg explored several reasons for the declining interest in and demand for architecture, including austerity measures reducing the demand for new construction; a perception of architecture and design as luxury goods; and low pay and sparse jobs spurring recent graduates to other, related fields.12 We would add a fear of defining and embracing new terms of measurement to this list.

While architecture’s decline has been troubling for many in our profession, we can produce momentum and raise the discipline’s profile by pursuing new directions and new niches for our skills. Defining and acting on these proposed new areas of measurement will create renewed value for architecture and may well open up entirely new opportunities.

Additionally, if we continue to focus on monetary gain and funding as the main measure of how “successful” architecture (or the architect) is, we are missing a key piece of what we do: serving the people who will use our buildings and spaces each day. While financial indicators are absolutely important for the economic sustainability of our careers and our field, directing the measurement of architectural output toward the success of human factors reframes the importance of architects in a meaningful and sustainable way.

It’s important to note that, while we believe these financial and human factors should be reprioritized, they remain intertwined. Commercial success for architects is bound up in commercial success for the developer and the occupant organization. Therefore, our job is increasingly to attract and retain ideal occupants; to satisfy them physically, emotionally, and spiritually; to capture their attention and improve their wellness (aka: provide delight). The better we can deliver a product that achieves these objectives, the better we will be compensated. Especially in this hyper-mobile age, when occupants can “vote with their feet” and leave lackluster environments for greener pastures, we’ll draw more proverbial bees with honey (or, perhaps, with fresh flowers on the meeting table) than ever before.

Over the last two decades, our industry turned to LEED to provide an alternative measure for buildings that prioritizes environmental conservation and low emissions. Today, the WELL standard is emerging as a companion building standard “focused exclusively on human health and wellness.”13 By emphasizing the importance of building performance from a people perspective, we continue to expose new avenues of architectural work like these. Now that we are approaching more and more sophisticated measurements of human factors performance, the potential to reconstruct the importance of architects and our work is finally a reality.

Measurement has always been integral to architecture, but its use and value are quickly expanding. A 2015 exhibit at the Storefront for Art and Architecture explored how we measure today, and how much data is available to be harnessed. Directing our new capacities wisely will not only make architecture more robust, it will also bring the profession up to speed with the quantification capabilities that prevail in so many other fields. After all, as a review of the Storefront exhibit points out, “Being measured, like being videotaped, is just another 21st-century condition.”14 Thoughtful implementation will allow us to elevate measurement beyond something banal and help create new, dynamic possibilities for our discipline.

We architects are trained in a unique skill set that, despite the often narrow ways in which it has traditionally been evaluated, is quite multifaceted and has a major impact on how people navigate their lives. In order to increase future prospects for architects and improve the effectiveness of our work every day, we would be wise to seriously consider how we might evaluate our buildings and spaces on their success in creating and cultivating delight. At this point, we take for granted the ability to quantify our power to create products with firmness and utility; why should we not also seek to understand and measure by this elusive third quality as best we can?

In order to reinvigorate our work, architects should look to Charles Darwin and the concept of “survival of the fittest.” While Darwin is best known as the father of evolutionary biology, he was also a habitual self-quantifier with an abiding interest in measuring and explaining feelings15; he poured his extensive research on this topic into the 1872 volume The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. (He could even be accused of aiming to quantify happiness.) As individuals, we must refine and expand our skills so that we can better adapt to changing circumstances and expectations. In order to remain relevant and beneficial, we cannot always hew to the same traditional practices. Instead, it is time to prepare for the next stage of architectural evolution. Vitruvius’s three elements have defined the success of architecture for centuries. While they form a timeless foundation for what we do, we should also follow Darwin’s insistence upon evolution and embrace new means for knowing and delighting our occupants.

This article originally appeared in Work Design Magazine.

References

University of Chicago Library News. “Firmness, Commodity, and Delight: Architecture in Special

Collections.” Last modified May 4, 2011. http://news.lib.uchicago.edu/blog/2011/05/05/firmness-commodity-and-delight-architecture-in-special-collections-exhibition

Kringelbach, Morten L. and Berridge, Kent C. “The Neuroscience of Happiness and Pleasure.”

Social Research 77.2 (2010): 659-678. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3008658

Gretchen Rubin. “The Happiness Project.” Accessed September 11, 2017. http://gretchenrubin.com/books/the-happiness-project/about-the-book

Hoffman, Jan. “On Top of the Happiness Racket.” The New York Times. February 26, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/28/fashion/28rubin.html

Marsh, Melissa. “Architecture in the Social Data Era.” Oculus. March 2015. http://www.nxtbook.com/naylor/ARCQ/ARCQ0215/index.php?startid=34#/34

Bersin, Josh. “Quantified Self: Meet the Quantified Employee.” Forbes. June 25, 2014. https://www.forbes.com/sites/joshbersin/2014/06/25/quantified-self-meet-the-quantified-employee/#27a9a70c5fe4

Mueller, Kristin and Marsh, Melissa. Multisensory Design: The Empathy-based Approach To Workplace Wellness. Work Design Magazine. April 20, 2017. https://workdesign.com/2017/04/multisensory-design-empathy-based-approach-workplace-wellness

Zeiger, Mimi. “Systems Thinking in Architecture.” Architect, April 27, 2011. http://www.architectmagazine.com/practice/systems-thinking-in-architecture_o

Lévy, Maurice. “Do not let fear kill the promise of Big Data.” Financial Times. September 1, 2015. https://www.ft.com/content/99b7f390-509d-11e5-b029-b9d50a74fd14

Silverman, Rachel Emma. “Bosses Tap Outside Firms to Predict Which Workers Might Get Sick.” The Wall Street Journal. February 17, 2016. https://www.wsj.com/articles/bosses-harness-big-data-to-predict-which-workers-might-get-sick-1455664940

Timberg, Scott. “The architecture meltdown.” Salon, February 4, 2012. http://www.salon.com/2012/02/04/the_architecture_meltdown

Delos. “WELL Building Standard.” Accessed February 26, 2016. http://delos.com/about/well-building-standard/

Schwendener, Martha. “Review: ‘Measure’ Investigates the Art of Quantifying.” New York Times. August 27, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/28/arts/design/review-measure-investigates-the-art-of-quantifying.html

Sweet, Matthew. “The Luxury of Tears.” 1843 by The Economist. April/May 2016. https://www.1843magazine.com/features/the-luxury-of-tears

Notes

-

University of Chicago Library News. “Firmness, Commodity, and Delight: Architecture in Special

Collections.” Last modified May 4, 2011. ↩

-

Kringelbach, Morten L. and Berridge, Kent C. “The Neuroscience of Happiness and Pleasure.”

Social Research 77.2 (2010): 659-678. ↩

-

Gretchen Rubin. “The Happiness Project.” Accessed September 11, 2017. ↩

-

Hoffman, Jan. “On Top of the Happiness Racket.” The New York Times. February 26, 2010. ↩

-

Marsh, Melissa. “Architecture in the Social Data Era.” Oculus, March 2015. ↩

-

Bersin, Josh. “Quantified Self: Meet the Quantified Employee.” Forbes, June 25, 2014. ↩

-

Mueller, Kristin and Marsh, Melissa. “Multisensory Design: The Empathy-based Approach To Workplace Wellness.” Work Design Magazine. April 20, 2017. ↩

-

Zeiger, Mimi. “Systems Thinking in Architecture.” Architect, April 27, 2011. ↩

-

Lévy, Maurice. “Do not let fear kill the promise of Big Data.” Financial Times. September 1, 2015. ↩

-

Silverman, Rachel Emma. “Bosses Tap Outside Firms to Predict Which Workers Might Get Sick.” The Wall Street Journal. February 17, 2016. ↩

-

Timberg, Scott. “The architecture meltdown.” Salon, February 4, 2012. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Delos. “WELL Building Standard.” Accessed February 26, 2016. ↩

-

Schwendener, Martha. “Review: ‘Measure’ Investigates the Art of Quantifying.” New York Times. August 27, 2015. ↩

-

Sweet, Matthew. “The Luxury of Tears.” 1843 by The Economist. April/May 2016. ↩