Displaying art in the workplace can elevate employee performance, mood, and physical well-being, as well as bolster interpersonal bonds between employees and clients. Dozens of research studies conducted in the United States and Europe throughout the past 10 years have identified myriad ways—from the practical to the unconscious—that installing thoughtfully-chosen art in the workplace can improve employee experience and achievement, and help to communicate the right message to guests. In this brief guide, experts from PLASTARC summarize the many positive effects certain kinds of art can bring to employees and visitors, and share ideas about how to choose the best art for the workplace.

Art as a tool for wayfinding, culture, and employee ownership

Workplaces can often feel like a maze of desks, hallways, and doors. Because our brains hold onto memorable environmental features, art can usefully function as a landmark, helping people traveling through a space to remember where they’ve been. It can also come in handy when providing directions.

Amidst many options for addressing branding and company culture in the workplace, art can help communicate key brand messages in a non-verbal way. For example, an organization that displays unusual artwork is likely to be seen as conducting business in less traditional ways of marketing less conventional products; art that seems based in multiple ethnic traditions can signal multicultural management practices; and art depicting well-known and high-prestige locations, such as the White House, can indicate a history of working with powerful allies.

By this same token, if the art in place illustrates issues of common concern and collective identity — such as environmentally-responsible behavior or pediatric health — it can support a feeling of unity, whether among employees or between an organization and its clients. Additionally, while work environments can sometimes feel like universes unto themselves, art in the workplace can serve as an outlet for highlighting local culture and community, creating a bridge between the workplace and its surroundings. Successful corporate collections often feature local artists and demonstrate direct reference to the proximate cultural milieu.

For organizations hoping to give employees a sense of agency in their workplace environments, allowing workers to choose and position their own art can supply them a feeling of control, which has been linked to enhanced professional performance at the individual, group, and organizational levels. Participatory murals take this a step further, allowing employees to interact with the art post-installation and on their own terms. In general, employees show the most attention to detail, process and manage information best, and show the highest levels of organizational citizenship when their workplaces both display art and have allowed input into its selection and placement.

Art’s role in employee stress, health, and performance

Akin to its proven rehabilitative influence in hospitals, art in the workplace

has also been shown to benefit employee well-being and performance. This is

significant, as the office can easily become a place of stress and tension,

and people become cognitively exhausted after prolonged periods of

highly-focused work. Viewing artwork, particularly realistic nature scenes,

helps workers restore mental energy and reduce stress. Unsurprisingly, both of

these effects boost brain performance. Seeing nature images in artwork has

also been linked to

lower levels of anger

in workplaces. One in four American workers report feeling chronically angry,

which has been linked to negative outcomes such as retaliatory behavior,

interpersonal aggression, poor work performance, absenteeism, and increased

turnover. People who work in environments decorated with

aesthetically-engaging art typically experience less stress and anger in

response to task-related frustration, and thus help to build a more

collaborative and enjoyable workplace.

Image via TurningArt. Click through for more details.

Interpersonal interaction also results from art that sparks discussion among employees. If creativity, innovation, and open conversations are elements of an organization’s purported culture, the placement of engaging artwork can help substantiate these values and make them visually available. Employees tend to feel more cooperative and open to considering differing points of view when exposed to images they find pleasing, including images of places to which they feel a connection — for instance, an employee in New York City looking at a beautiful photo of Central Park, or an employee in London seeing a painting of the English countryside.

Art objects have also been shown to hold high emotional value for viewers, more than paintings, which are understood as extensions of their makers, representing a uniquely manifest, personal expression. Objets d’art — or, curated art objects — placed across the workplace is one technique for encouraging reflection and the resultant communal discussion, as well as instilling visual and material interest throughout the work environment at low cost. These can be deployed in large numbers and at multiple scales, and offer personality without preciousness or personal narrative.

If creativity, innovation, and open conversations are elements of an organization’s purported culture, the placement of engaging artwork can help substantiate these values and make them visually available.

Art, like nature, is significant in its ability to transport the viewer to a different mental plane — an experience often described as awe, or “experiencing perceptual vastness: the sense that one has come upon something immense in size, number, scope, ability, or social bearing.” When people experience awe, it can significantly lower levels of inflammation that can lead to chronic illnesses including diabetes, depression, and cardiovascular disease. It can also stimulate a more efficient processing of information, allowing people to feel less rushed, more patient, and more willing to volunteer. In healthcare settings, the display of nature scenes has been linked to lower levels of patients’ perceived pain, stress, anxiety, fatigue, and general distress, and is usually gauged to be a “positive distraction” (one that elicits good feelings and holds attention without causing stress, thereby blocking worrisome thoughts). Patients also socialize more with each other, are less restless and quieter when nature scenes are on view.

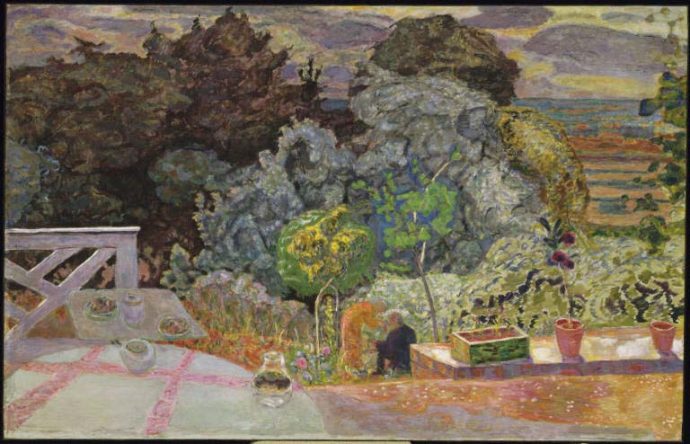

The task of choosing the “right” art

Well-considered art decisions for the workplace will take into account the particular effects of content, texture, scale, and positioning. Positive-mood inducing images of the natural world often feature grassy areas interspersed with clumps of deciduous trees, green foliage, a view to the horizon, a gently flowing body of water, and a foreground area into which the viewer might step. For the best effect, these views should be from a slightly elevated position — like looking down into a verdant valley. When it comes to depictions of humans, conjuring images of our distant past — in the form of visualizing older generations — has been linked to improved performance on intelligence tests. Artwork that shows people being cared for reduces strong responses to threatening or stressful situations by reminding us of feeling loved. This state of mind promotes more effective functioning during stressful situations, and greater activation of soothing mental resources afterward.

One glance at this verdant scene and we’re already feeling better! Image — “The Terrace”, by Pierre Bonnard — via The Phillips Collection.

Most positively-received artworks have a moderate amount of visual complexity; impressionist paintings are a good example. Art that appears too simple or too complex is more likely to have a negative influence on mood. The same goes for colors and patterns that are not so familiar as to be boring, but not so unfamiliar as to be confusing. Horizontal and vertical lines (as opposed to diagonals) and curving lines (as opposed to straight ones) are easiest to process, as are symmetrical (versus asymmetrical) images. Pleasing and interesting visuals are recommended over challenging ones — viewers generally prefer to feel that they understand a work of art. To this end, representational or figurative art is a better choice than abstract pieces.

Companies choosing to express their brand identities through super-graphics and other collateral may achieve some of art’s benefits, such as visual interest and collective reference, though more subjective responses like tranquility and curiosity will likely be left out. But, implementing art as a tool for improving occupant experience is not so clear-cut a task, as the body of evidence regarding art’s nuanced intellectual, emotional, and physical influence proves. This is particularly true in workplaces, each coming with unique spatial constraints, cultural considerations, and organizational objectives. Workplace strategy consultancies such as PLASTARC and workplace art rental services such as TurningArt can provide ideas and resources for the strategic incorporation of art in the workplace, including guidance on what scale, texture, color, and content would best serve the needs of particular people and spaces.

Melissa Marsh, Sally Augustin, April Greene, Teresa Whitney, Jason Gracielli, and Devin Vermuelen also contributed to this article.

This piece was first published by Work Design Magazine.

Works Cited

Dina Abdulkarim and Jack Nasar. 2014a. “Are Livable Elements Also Restorative?” Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 38, pp. 29-38.

Dina Abdulkarim and Jack Nasar. 2014b. “Do Seats, Food Vendors, and Sculptures Improve Plaza Visitability?” Environment and Behavior, vol. 46, no. 7, pp. 805-825.

2007. Bar and M. Neta. 2007. “Visual Elements of Subjective Preference Modulate Amygdala

2008. Activation.” Neuropsychologia, vol. 45, no. 10, pp. 2191-2200.

Michal Bilewivz and Jaroslaw Klebaniuk. 2013. “”Psychological Consequences of Religious Symbols in Public Space: Crucifix Display at a Public University.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 35, pp. 10-17.

“Brain’s Response to Threat Silenced.” 2014. Press release, University of Exeter.

Penelope Craw, Louis Leland, Michelle Bussell, Simon Munday, and Karen Walsh. 2006. “The Mural as Graffiti Deterrence.” Environment and Behavior, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 422–34.

Ann Devlin and Jack Nasar. 2012. “Impressions of Psychotherapists’ Offices: Do Therapists and Clients Agree?” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 118-122.

Denis Dutton. 2009. The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure and Human Evolution. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Anne-Marie Emond. 2008 “Contemporary Art and the General Public in Museums.” In Kenneth Bordens (ed.). “Proceedings of the 20th Biennial Congress of the International Association of Empirical Aesthetics.” http://www.iaea.org

Peter Fischer, Anne Sauer, Claudia Vogrincic, and Silke Weisweiler. 2011 “The Ancestor Effect: Thinking About Our Genetic Origin Enhances Intellectual Performance.” European Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 11-16.

Bob Giddings, Jenny Thomas, and Linda Little. 2013. “Evaluation of the Workplace Environment in the UK, and the Impact on Users’ Levels of Stimulation.” Indoor and Built Environment, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 965-976.

Robert Gifford. 2014. Environmental Psychology, 5th Edition. Optimal Books: Colville, WA.

Kathy Hathorn and Upali Nanda. 2008. “A Guide to Evidence-Based Art.” Center for Health Design, http://www.healthdesign.org

Craig Knight and Alexander Haslam. 2010. “The Relative Merits of Lean, Enriched, and Empowered Offices: An Experimental Examination of the Impact of Workspace Management Strategies on Well-Being and Productivity.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 158-172.

Ursula Krentz and Rachel Earl. 2013. “The Baby as Beholder: Adults and Infants Have Common Preferences for Original Art.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 181-190.

Robert Kreuzbauer, Dan King, and Shankha Basu. 2015. “The Mind In the Object—Psychological Valuation of Materialized Human Expression.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, vol. 144, no. 4, pp. 764-787.

Byoung-Suk Kweon, Roger Ulrich, Verrick Walker, and Louis Tassinary. 2008. “Anger and Stress: The Role of Landscape Posters in an Office Setting.” Environment and Behavior, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 355-381.

Annukka Lindell and Julia Mueller. 2011. “Can Science Account for Taste? Psychological Insights Into Art Appreciation.” Journal of Cognitive Psychology, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 453-475.

Yui Motoyama and Kazunori Hanyu. 2014. “Does Public Art Enrich Landscapes? The Effect of Public Art on Visual Properties and Affective Appraisals of Landscapes.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 40, pp. 14-25.

Upali Nanda. 2011. “Impact of Visual Art on Waiting Behavior In the Emergency Department.” Published by the Center for Health Design, http://www.healthdesign.org

Upali Nanda, Sarahane Eisen, and Veerabhadran Baladandayuthapani. 2008. “Undertaking an Art Survey to Compare Patient Versus Student Art Preferences.” Environment and Behavior, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 269-301.

Michael O’Neill. 2010. “A Model of Environmental Control and Effective Work. Facilities, vol. 28, no. 3/4, pp. 118-136.

George Newman, Daniel Bartels, and Rosanna Smith. 2014. “Are Artworks More Like People Than Artifacts? Individual Concepts and Their Extensions.” Topics in Cognitive Science, vol. 6, pp. 647-662.

Anna Pecchinenda, Marco Bertamini, Alexis Makin, and Nicole Ruta. 2014. “The Pleasantness of Visual Symmetry: Always, Never or Sometimes.” PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 3, http://www.plosone.org

Donald Polzella, Stephanie Hammar, and Chad Hinkle. 2005. “The Effects of Color on Viewers’ Ratings of Paintings.” Empirical Studies of the Arts, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 153–63.

Melanie Rudd, Kathleen Vohs, and Jennifer Aaker. 2012. “Research Paper No. 2095: Awe Expands People’s Perception of Time, Alters Decision Making, and Enhances Well-Being.” stanford.edu PDF.

Suzanne Segerstrom and Sandra Sephton. 2010. “Optimistic Expectancies and Cell-Mediated Immunity: The Role of Positive Affect.” Psychological Science, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 448-455.

Shiota, D. Keltner, and A. Mossman. 2007. “The Nature of Awe: Elicitors, Appraisals, and Effects on Self-Concept.” Cognition and Emotion, vol. 21, pp. 944-963.

Suzanne Shu and Claudia Townsend. 2014. “Using Aesthetics and Self-Affirmation to Encourage Openness to Risky (and Safe) Choices.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 22-39.

Jennifer Stellar, Neha John-Henderson, Craig Anderson, Amie Gordon, Galen McNeil, and Dacher Keltner. “Positive Affect and Markers of Inflammation: Discrete Positive Emotions Predict Lower Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines.” Emotion, in press.

Kamila Svobodova, Petr Sklenicka, Kristina Molnarova and Jiri Vojar. 2014. “Does the Composition of Landscape Photographs Affect Visual Preferences? The Rule of the Golden Section and the Position of the Horizon.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 38, pp. 143-152.

Ulrich and L. Gilpin. 2003. “Healing Arts: Nutrition for the Soul.” In S. Frampton, L. Gilpin, and P. Charmel (eds.), Putting Patients First: Designing and Practicing Patient-Centered Care,

San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 117-146.

Jennifer Veitch. 2012. “Work Environments.” In Susan Clayton (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology. Oxford University Press: New York, pp. 248-275.

Daphne Wiersema, Job van der Schalk, and Gerben van Kleef. 2012. “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue? Need for Cognitive Closure Predicts Aesthetic Preferences.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 168-174.