Whose space is this?

A more equitable world starts with space for everyone

How do you define equity? Sometimes things that may feel equitable actually aren’t, or vice versa. In this month’s “On Our Minds…”, we take a closer look at the underappreciated role of space in creating and maintaining equity—and the opposite. Do scroll on, won’t you?

On our minds

No two spaces are equal—even if they might look as if they are. From the bus stops and lunch counters of the civil rights era to the painted streets and occupied city squares of this past summer, the pursuit of equity has always been tied to space—who controls or has the right to use it, proximity to other desirable spaces, infrastructure and amenities offered, and so on. In the last decade or so, there has been growing interest in the relationship between space and social justice.

The ways that spaces are designed, distributed and utilized express either equity or inequity. This is perhaps most vividly noticeable when highlighted through acts of protest that revolve around access to certain spaces or through the uneven application of practices like hostile architecture. It also expresses itself in less remarkable ways.

Whether it’s the spot closest to the exit in a subway car or the office closest to the board room, every environment has locations of preferred experience. Without intervention to the contrary, access to these plum spots usually breaks down along existing hierarchical lines. How can designers account for these inequities in ways that make things better—more equitable and more welcoming to diverse people and preferences? As steadfast advocates of the value of measurement, we think the answer lies in collecting better data and finding better ways to use it.

Most aspects of the human experience—from thermal comfort to engagement—can be quantified in relation to space. As part of the growing discipline of people analytics, such quant efforts present new opportunities to optimize for equity—but only if practitioners use them well. The way that data is collected and then represented plays a critical role in figuring out what the problems are and how they should be fixed. Data visualizers and mapmakers shape our understanding of challenges in our societies, systems and workplaces.

Sometimes, spatial factors are intentionally amplified. For example, the seating chart presented when buying tickets to a concert—an event at which the experience is the entire point—might have a dozen different tiers of pricing, highlighting the distinction and allowing people to choose the desired level of experience. In other situations—such as in political map-making—spatial (or social) relationships may be erased in harmful ways.

The decision to either highlight or minimize the differences between places is a unique kind of power, and is one that is often underappreciated. It is impossible to fix a problem that one does not see, and there are assumptions about what does and does not matter baked into every representation of data.

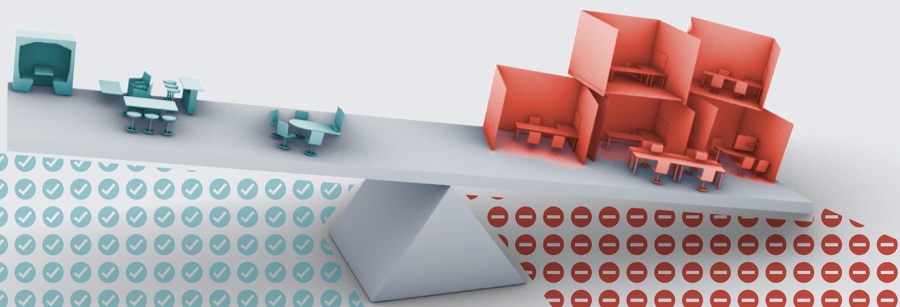

In workplaces, there is a tendency to ignore the differences between locations. While most people acknowledge the distinction between a corner office and a seat in the bullpen, fewer pay much attention to experiential differences that are less obviously tied to status, such as sitting in the middle of a bench seat versus at the end. Yet, such differences shape the experience of occupants in ways that make a space more or less desirable, and are more quantifiable than is typically acknowledged.

Physical differences in space don’t just affect our bodies—they affect our minds as well. We have written previously about how factors like prospect (the ability to see and be seen by other occupants) and propinquity (nearness in space or connection) can impact the ability of people to perform well in a space. It is important to question whether these elements of design reinforce hierarchies in ways that are harmful.

On the scale of localities, tools like GIS can be valuable in visualizing metrics that can have a major impact on one’s quality of life or ability to participate in society. They can make visible the tremendous value of small investments in the environment that pay off for individuals and society. For a compelling example of this, take a look at the Million Dollar Blocks exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art by Laura Kurgan and Sarah Williams of Spatial Information Design Lab at Columbia University, who use information graphics to convey the cost of incarceration as compared to civic investments such as community centers in urban neighborhoods for young people.

At the level of buildings and offices, there is a lot of room for improvement in the way we measure and analyze equity. Thinkers like Mindy Thompson Fullilove, who we had the pleasure of getting to know at a panel we moderated in 2015, are pushing architects to think harder about their role in either maintaining or challenging the status quo. The American Institute of Architects took a positive step by releasing its guide to equitable practices, but the profession as a whole still has a lot of growing to do.

One of the tools we use to help our clients understand the impacts of their spatial strategy is a user experience plan analysis. It makes visible the many layers of hierarchy that may otherwise remain unseen in a typical office. For example, sitting 10 feet from a window is very different from 40 feet. A private office may grant someone 4 or 5 times as much space as a desk. In addition, there is much more to the human experience than is shown on the typical office floor plan. As we noted in our presentation to the Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA), the totality of the human sensory experience can and should be considered in every design.

Quantifying the way people experience their spaces gives an organization the opportunity to ask more interesting questions about equity and the spaces they provide. For example, if two people have the same job, but one of them is assigned to a seat much closer to the window, should the other be given more space? If two people do similar work, but one's seat is based next to a busy hallway, are they really receiving the same experience? With ubiquitous teleworking, what are an organization's responsibilities for equitable environments at home and outside the office?

The geometry of a space expresses values and priorities that may or may not be in step with an organization's culture—or even basic concepts of fairness. If design is to play a positive role in creating equity in our society, we must begin with an honest look at the different ways that people experience space, and the often-unequal ways in which space is allocated.

Ready to stop telling your team where to sit to do their work? Check out our next webinar on ABW & Coworking.

From the archives

Space is just one of the ways that hierarchy is made and maintained in the workplace. Back in early 2019 we asked, “In Shared Workplaces, Who Makes The Rules?”, which pondered the power of norms to influence individual and group behavior.

A little further back, we wrote about the role of environmental psychology in shaping workplace experience. Quant-heads that we are, it gave us a chance to share a bit more about our philosophy of measuring the seemingly unmeasurable.

That’s all for this month. Thanks for making room for us in your day. Drop us a note to let us know how your space could be more equitable. In the meantime, we'll be celebrating Black History Month by indulging in some of our favorite Tiny Desk concerts including Tank and the Bangas.

In Case You Missed It

Our plate has been as full as ever! Here are a few recent happenings that might be of interest to the spatial-minded.

Evolving Your Portfolio

Our first webinar of 2021 discussed multi-market strategies emerging in the age of viable mass telework.

Sharing Space: Coworking Goes B2B

Thought leaders discuss how organizations can adopt principles of corporate-to-corporate coworking to minimize expenses, build flexibility and enhance user experience (UX).

France Scraps Lunch@Desk Ban

As part of the effort to combat COVID, French workers will, for the moment, be able to eat lunch at their desks.

Onward and Upward

We’ve re-published this guide to choosing a space that meets all of your team’s needs, now and in the future.

The Cloffice Has Arrived

In a sign of the times, the New York Times has now used the word “cloffice” to refer to a tiny home office.

10 Pioneering Black Architects

In celebration of Black History Month, learn about the work of these great designers.

PLASTARC is Hiring

Passionate about making workplaces better for people and organizations? Drop us a line!

Looking Ahead

We’re looking forward to a spring full of opportunities to learn and share, including more PLASTARC webinars. Won’t you join us?